Archaeology and Looting

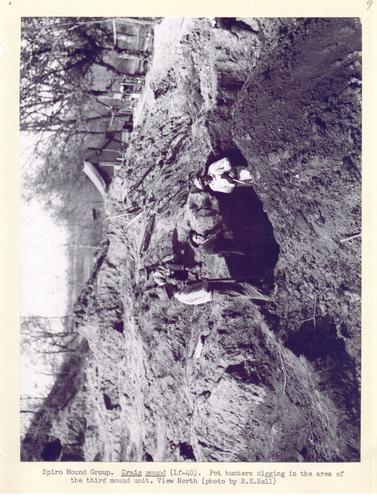

Unfortunately, much of what we understand about the Spiro site comes to us only in bits and pieces. This site remains the location of one of the largest and longest episodes of looting at any American archaeological site in history. First identified in 1914 by Joseph Thoburn, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, the mounds were part of the Choctaw Nation land allotment. Divided into at least four allotment partitions, the Spiro site was dispersed to Choctaw freedmen. At this time, the owners forbid all digging on the property, forcing Thoburn to abandon his attempted excavation. By 1933, however, this restriction was reversed. Needing the money, the owners now leased the land to a group of commercial diggers calling themselves the Pocola Mining Company (PMC). Having no respect for the site or the Caddoan people who created it, they dug with reckless abandon. Their only goal was to extract as much material from the mound as possible. Soon, the PMC discovered the most unique feature ever revealed in North America. They had found a hollow chamber, or Spirit Lodge, in the mound’s interior, containing thousands of freshwater pearls, eight hundred engraved and unengraved marine shell cups, stone and wooden statuary, basketry, feathered textiles, masks, large copper plates, and countless other items. “Moving swiftly, these men grabbed all the ancient relics they could sell and tossed the textiles, pot sherds, broken shell, and cedar elements onto the ground.” As described by Forrest E. Clements, head of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, in 1945, “Sections of cedar poles lay scattered on the ground, fragments of feather and fur textiles littered the whole area; it is impossible to take a single step in hundreds of square yards around the ruined structure without scuffing broken pieces of pottery, sections of engraved shell, and beads of shell, stone, and bone.”20

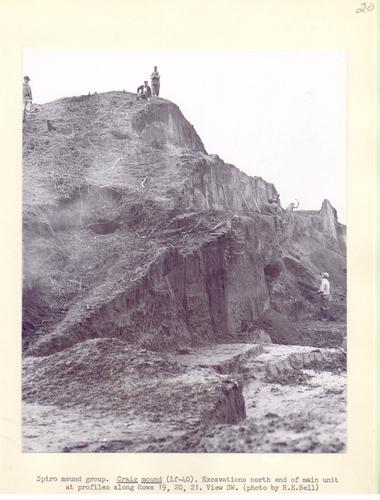

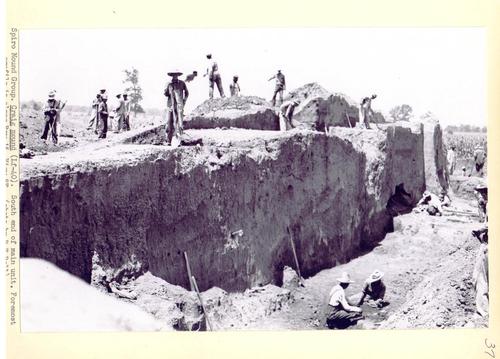

To save what remained of the site, Oklahoma passed the state’s first antiquities laws in 1935. They required all excavations to be licensed through Forrest Clements and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Oklahoma. Denying all other licenses to the site, Clements collaborated with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to exhume what was left of the mound. From 1936 to 1941, a joint excavation was undertaken by the University of Oklahoma, the University of Tulsa, the Oklahoma Historical Society, and the Woolaroc Museum. Even after two years of looting, what was discovered at the Craig Mound still remains the largest assemblage of material ever revealed at a single Mississippian site.

WPA excavation

Excavation at south end of main unit

Lear Howell and his wife with looted artifacts from the Spiro and other surrounding sites

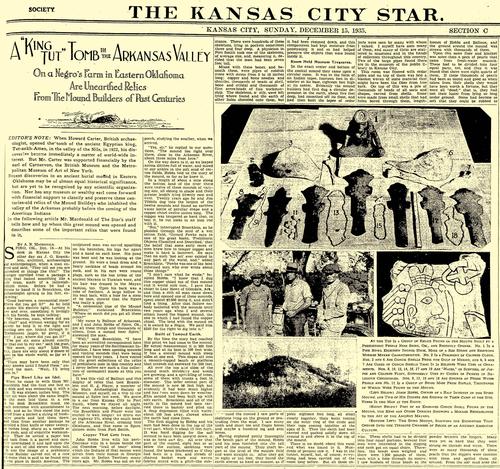

“A ‘King Tut’ Tomb in the Arkansas Valley”

Destroyed mounds at Spiro site

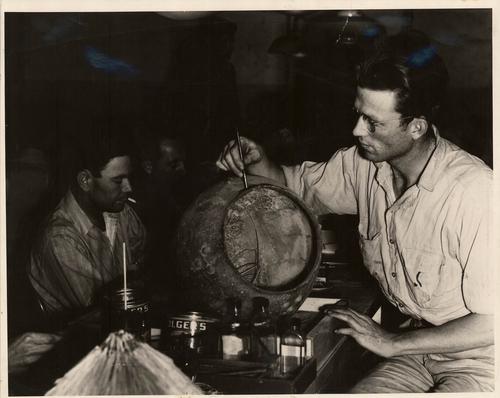

Forrest Clements

Four WPA supervisors

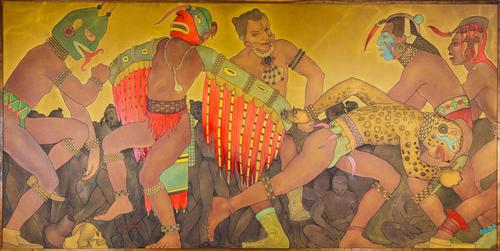

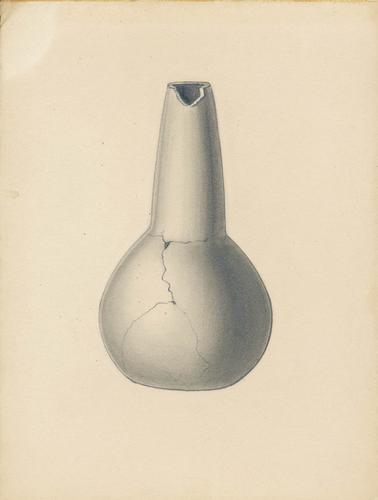

WPA Drawing

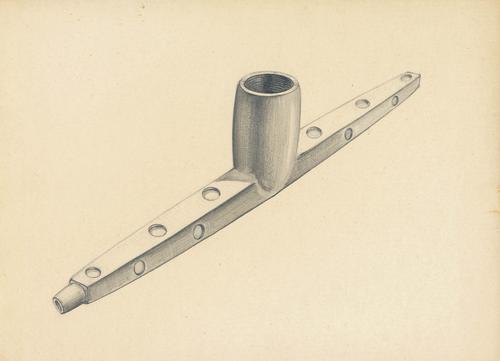

WPA Drawing of T-shaped pipe

Craig Mound in the snow