Cahokia

Illiniois

The largest Mississippian ceremonial center known today is Cahokia. Located just outside St. Louis, Missouri, this city had a population of 10,000 to 20,000 people, contained nearly 200 earthen mounds, and covered five square miles.

Founded around AD 1050, this site is divided into five separate phases: Lohmann (AD 1050–1100), Stirling (AD 1000–1200), Moorehead (AD 1200–1275), Sand Prairie (AD 1275–1350), and Oneta (AD 1350–1650). Each phase is identified by distinct ceramic types and style of architecture.

The city was palisaded (walled) and had a large grand plaza that was the equivalent of thirty-five football fields. It also contained the third-largest pyramidal mound in all the Americas. Known as Monk’s Mound, it measures one hundred feet high and took nearly 150 years to complete. The Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán and the great pyramid at Cholula, both located in Mexico, are the only pyramids larger than Monk’s Mound.

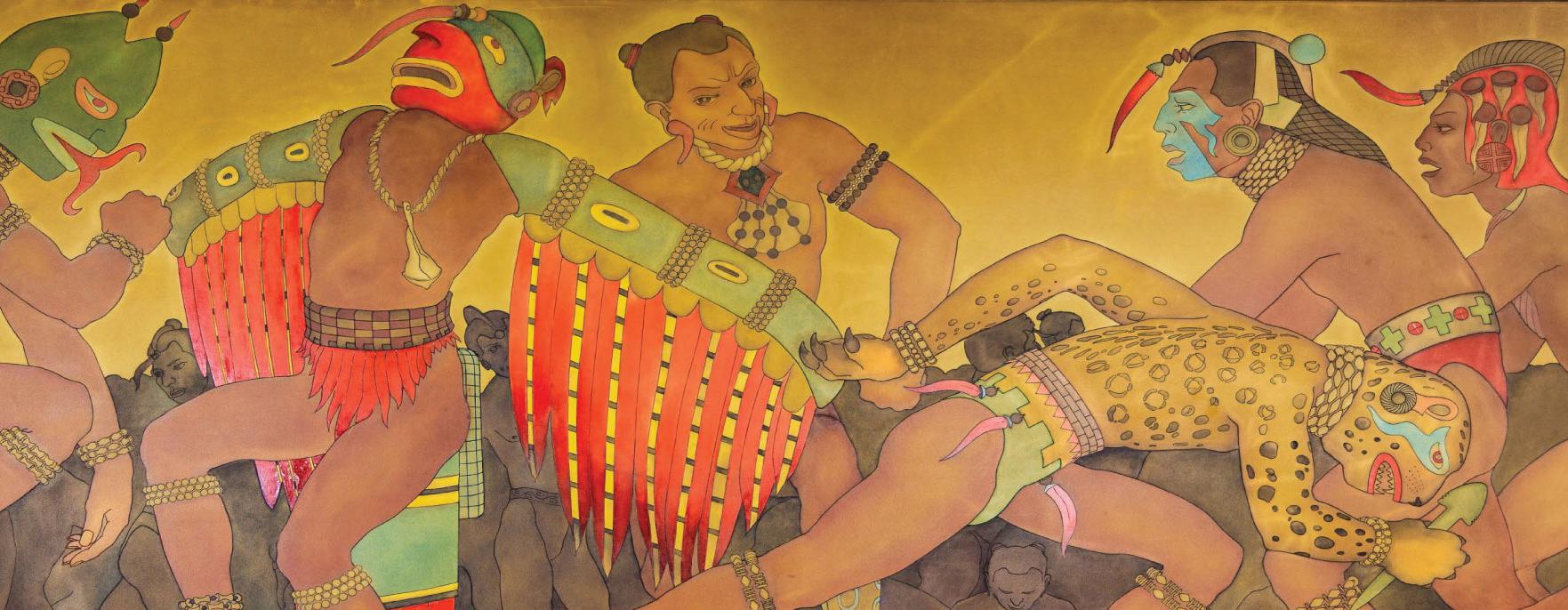

Cahokia was also the likely epicenter of an artistic tradition referred to as Braden. Braden is a highly refined artistic style known for its representation of Morning Star and Earthmother as well as its depictions of plants, animals, and humans with references to body painting and tattooing. Objects created in this style are found at other large ceremonial centers across the eastern half of North America—including Moundville in Alabama, Etowah in Georgia, and Spiro

in Oklahoma.

Moundville

Alabama

Located on the banks of the Black Warrior River thirteen miles south of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Moundville was established around AD 1000 and rose in prominence to become one of the principal ceremonial centers in the Mississippian world.

Comprising nearly thirty mounds, Moundville can be divided into five separate phases, each defined by a distinct ceramic style: West Jefferson (AD 1020–1120), Moundville I (AD 1120–1260), Moundville II (AD 1260–1400), Moundville III (AD 1400–1520), and Moundville IV (AD 1520–1650).

The city center was surrounded by a large defensive wall and sat on nearly 185 acres. The largest mound, Mound A, had a base of two acres and was approximately twenty feet high. On top of each mound sat various public and religious structures as well as the chiefly residence. Historical parallels suggest that Moundville was originally built as a sociogram—an architectural depiction of a social order based on ranked clans. Paired groups of mounds along the plaza’s edge were associated with specific clans, arranged according to social power and prestige.

By AD 1300, however, Moundville had undergone substantial change. The population rapidly diminished, the number of burials increased, and the large defensive walls were demolished. It appears the site had transformed from a large population center to a necropolis—a regional repository for the deceased.

Etowah

Georgia

Etowah was a large Mississippian center constructed about the same time as Cahokia and Moundville. It is in present-day Georgia and sits on the banks of the Etowah River in Bartow County, just south of Cartersville. Containing six mounds, it was the largest known ritual center in the region from AD 1000 to –1550.

Etowah is unique because it saw repeated instances of abandonment and repopulation. The first period of abandonment occurred in AD 1200 and lasted for nearly fifty years. It was rebuilt in AD 1250. This period of repopulation is known as the Wilbanks phase (AD 1250–1375). During this time, the site saw the enlargement of previously created mounds as well as many newly-constructed ones. The largest, Mound C, served as the mortuary facility for Etowah’s elite and included objects and iconographic imagery matching other regional styles—namely Braden.

By AD 1375, archaeological investigations indicate that the region was consumed with warfare and the city sacked. Following this, it was once again abandoned for nearly 100 years. When it rose once more, it was under the rulership of a new chiefdom. This new chiefdom was visited by Hernando de Soto in August 1540. During this trek, one of his chroniclers mentioned the Etowah site—referring to it as Itaba.

Kincaid

North of the Cumberland Valley

The area known as the Cumberland has one of the densest concentrations of mound sites from the Mississippian Period. The most notable mound site in this area is called Kincaid. Located in Brookport, Illinois, this site contained 19 mounds and was occupied between AD 1000 – 1400. Like the other eastern mounds, it was palisaded. It is believed that this site was the seat of regional politics during this period as it maintained a close trading relationship with Cahokia and the other mound sites in the Cumberland Valley.

Evidence indicates that the most common source of food was deer, bear, elk, turkey, and the eastern box turtle. Corn (maize) was the most harvested plant, but others, such as sunflowers, squash, beans, hickory nuts, and acorns were also utilized. This region had easy access to salt and mineral springs, which made it a powerful trade zone.

Just like Cahokia, Etowah, Moundville, and Spiro, by 1450 the site had been abandoned and replaced by scattered fortified villages. The fact that so many cities and towns were being abandoned gives rise to the conclusion that a common event was impacting every population group. This event was likely environmental and brought on by what is known today as a Little Ice Age. This Little Ice Age would have change weather patterns—effecting temperature, rain, and animal populations.

Spiro

Oklahoma

Located in Le Flore County, Oklahoma, Spiro is one of North America’s most important, but little known, ancient cultural and religious centers. Containing twelve mounds and a population of several thousand, it was physically unremarkable when compared to many other North American Mississippian sites. It is not the largest center ever discovered, nor did it have the biggest population. It also was not palisaded, as were the ceremonial centers of Cahokia, Moundville, and Etowah. What made it unique were the thousands of ceremonial objects found in an earthen Hollow Chamber—something not seen anywhere else in North America.

It was divided into different occupation phases beginning with the Evans Phase (AD 950 – 1100), Harlan phase (AD 1100 – 1250), Norman Phase (AD 1250 – 1350), and concluding with the Spiro Phase (AD 1350 – 1450).

The people of Spiro people relied on a wide variety of animals for meat, including deer, elk, turkey, fish, turtles, geese, ducks, squirrels, opossums, raccoons, and other small mammals. The Spiro people did not rely on maize as their primary cultivated crop like the inhabitants of the other ceremonial centers. Instead, they harvested chenopod (quinoa), maygrass, barley, and knotweed. This was supplemented with nuts and other wild plants.

After AD 1450, the site and region underwent considerable cultural and environmental changes. Artifacts found during this period reflect a major shift and resemble those typical of groups living on the Plains, such as the Wichita. These differences in food cultivation and mound construction often leave scholars defining this region, and site, as Caddoan and not specifically Mississippian. However, it is unquestionable that Spiro shared the same iconography and belief system as the other Mississippian Ceremonial Centers.